By Sonia Trickey, Deputy Headteacher at Pilgrim Pathways School

Teachers at The Pilgrim Pathways School were visited by the Vicky King OT from Brainbow at Cambridge University Hospitals this week.

When a young person is recovering from cancer or other chronic conditions, they often suffer from chronic fatigue. How do we support students to manage this on their return to school? Vicky King, Occupational Therapist from Brainbow (a service at CUH that specialises in rehabilitating children with brain injuries) shared her conisderable expertise and wisdom about how to manage symptoms in school.

One of the best aspects of working as part of a multi-disciplinary team is the access we have to experts beyond our field. This week, Occupational Therapist Vicky King, from Brainbow at Cambridge University Hospitals—an organization dedicated to rehabilitating children in the East of England who have brain tumours—spoke to us about supporting children suffering from unhealthy fatigue.

We’ve all arrived at work after a busy weekend, nursing a cold, and struggled through the day. It’s hard to concentrate, you feel both too hot and too cold, time seems to stand still, and even though you’ve inhaled a packet of chocolate digestives, you’re still peckish for something more. All you want is your bed: an early night will put everything right. This is healthy fatigue—with a little TLC, it resolves.

Vicky explained that chronic fatigue does not resolve. You feel like this every day, no matter how good your self-care routine or how much you sleep. The smallest activities can drain you—brushing your teeth, making a cup of tea, or picking up a few items at the shop.

Fatigue isn’t just caused by physical activities. Mental and emotional tasks can be just as draining, and the environment itself can also impact a person’s energy levels e.g. too noisy, too bright, too busy.

In turn, fatigue affects our emotions and our cognition as well as our physical abilities —we’re easily overwhelmed, less able to cope, and more prone to negative thought loops when we’re tired. And have you ever tried to do anything cognitively demanding on three hours of sleep? It takes twice as long, you do it half as well, and the next day, it makes no sense at all!

These are the levels of fatigue students recovering from serious illnesses, such as cancer, may experience, compounded by the chronic anxiety that comes with the uncertainty of a severe medical diagnosis.

At this point, you might wonder, why would anyone come to school feeling like that? Children and young people (CYP) diagnosed with life-threatening illnesses lose significant portions of their childhood. A mother I spoke to a few months after her son’s cancer diagnosis said, “It’s not just the cancer, it’s a series of losses.” CYP miss out on learning, friendships, and co-curricular passions like football, drama, or prom planning committees.

School is the centre of most CYP’s social, intellectual, and community life. It’s also a protective factor against the isolation and mental health burdens that accompany a life-threatening diagnosis.

If CYP are not supported to attend school, even minimally, throughout their treatment and recovery, they risk never returning at all as the gaps grow wider. 80% of CYP with cancer report fatigue, which can persist years after treatment. Fatigue is often cited as the most distressing treatment-related symptom and the main barrier to returning to normal activities (Hinds et al., 2000). This leads to limited participation and a diminished quality of life (Wilkinson et al., 2018; van Markus-Doornbosch et al., 2020). Although we can’t take away fatigue with a magic wand, we can put into place strategies that help the child maintain energy levels to do what they want throughout the day.

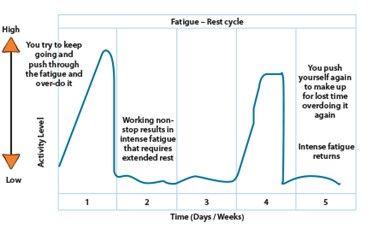

While exercise, activity, and social engagement are important in recovery, Vicky advises against the "boom and bust" cycle, where overexertion leads to prolonged recovery times. Doing ‘too much’ on one day then leads to a ‘crash’ where nothing is done the next day. Instead we aim for average levels of activities across the week.

She suggests organizing activities around five principles:

She referenced Christine Miserandino’s Spoon Theory, which imagines a finite number of “spoons” (units of energy) available each day. Each activity—no matter how mundane—uses spoons. Once the spoons are used up, they’re gone. This metaphor illustrates the constant planning, negotiation, and compromise CYP with chronic fatigue face: Do I shower or cook eggs? If I swap eggs for instant porridge, can I manage tea as well?

Teachers need to respect the CYP’s limited energy. For every activity completed, something else may have been sacrificed.

Vicky emphasized the need for a shared understanding across the child, family and school. Fatigue levels can fluctuate daily or even hourly. Plans should be dynamic and flexible. She also encouraged reframing how we talk about fatigue to avoid negativity and make sure the child can express the spectrum of how they are feeling.

For example:

Rather than lose an activity, help CYP choose an activity.

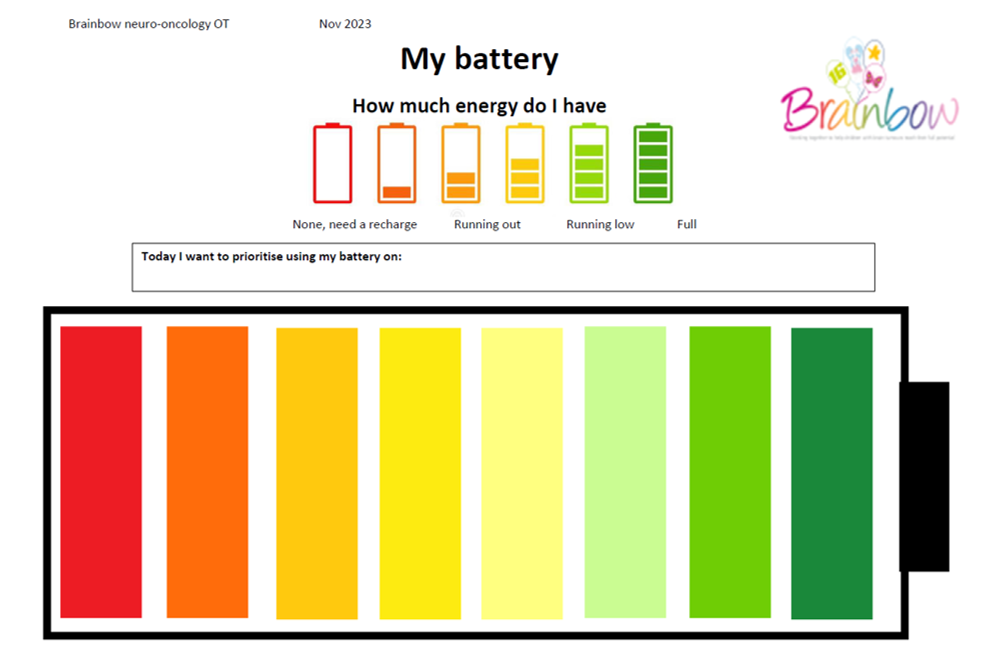

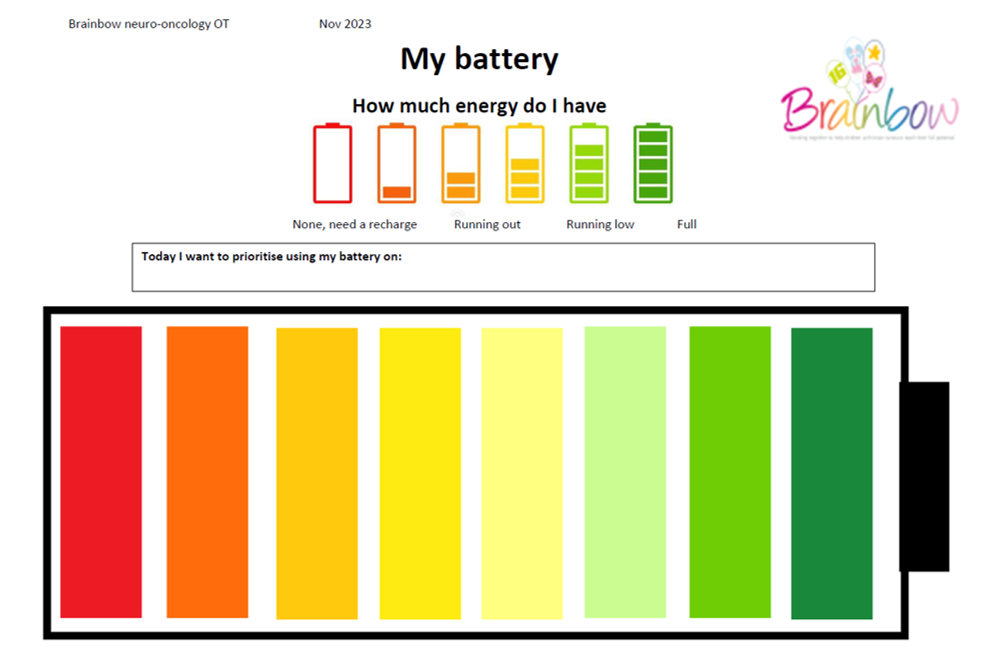

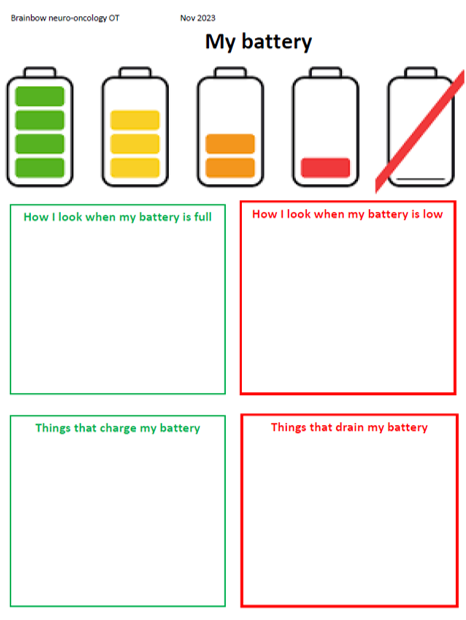

Vicky suggested the metaphor of a battery needing to recharge as a way to discuss fatigue. This could also be ‘fuel’, ‘juice’ or ‘spoons’. Perhaps a lesson in the classroom is draining too much energy and could be completed in a quieter space. Discuss what helps them to recharge —like fresh air, quiet time, or a quick snack— which might help boost energy for the next task. The lower they are on the battery the more of a recharge they might need.

She encouraged spending time with the CYP identifying what are their unique signs of tiredness at each stage of their energy. They might fall asleep when they are in red, but at amber they might just seem grumpy, or yawning. At yellow they might start looking more distracted or fiddling more. Everyone is different! You might need to point these things out for a long time before the CYP can identify it themselves, so labelling it on the battery visual can help.

She encouraged normalizing conversations about energy levels – modelling yourself about how it feels, what drains you and what you look like so that the child learns how to express their needs as well:

This framework teaches CYP self-regulation.

A SENCO or pastoral lead could use a visual plan to support CYP in managing their fatigue and share it with teaching staff.

Vicky encourages schools to work collaboratively with CYP and family to help them manage their fatigue. She advocates a robust yet cautious approach, urging schools to plan carefully, help CYP prioritize what matters to them, and rest assured that by keeping CYP connected to their schools, they’re supporting their recovery journey.